Narmada Poojari

Abstract The purpose of this paper is to introduce the concept of Svabhāva, its historical locatedness in the non-Vedic, atheist traditions of Buddhism, and the materialistic schools of Cārvāka /Lokāyata. Svabhāva as a religio-philosophical concept has been cursorily treated or even completely ignored by contemporary scholars in relation to premodern debates across traditions. Svabhāva has been variedly interpreted as different traditions. The Śāstras of the Vedic tradition which particularly deal with the regulation of human conduct and nature presupposes an underlying apriori fixed, determined, changeless human nature (svabhāva) which is opposed to its traditional conception in the non-Vedic traditions. This paper lays out the framework to extend the scope of the notion of svabhāva beyond its non-Vedic origins and laws of nature or causality to understanding the central intent and implicit assumption on human nature in the dominant śāstric texts which caused them to create a hierarchical model of classifying human beings based on certain presupposed inherent characteristics.

Abstract The purpose of this paper is to introduce the concept of Svabhāva, its historical locatedness in the non-Vedic, atheist traditions of Buddhism, and the materialistic schools of Cārvāka /Lokāyata. Svabhāva as a religio-philosophical concept has been cursorily treated or even completely ignored by contemporary scholars in relation to premodern debates across traditions. Svabhāva has been variedly interpreted as different traditions. The Śāstras of the Vedic tradition which particularly deal with the regulation of human conduct and nature presupposes an underlying apriori fixed, determined, changeless human nature (svabhāva) which is opposed to its traditional conception in the non-Vedic traditions. This paper lays out the framework to extend the scope of the notion of svabhāva beyond its non-Vedic origins and laws of nature or causality to understanding the central intent and implicit assumption on human nature in the dominant śāstric texts which caused them to create a hierarchical model of classifying human beings based on certain presupposed inherent characteristics.

An excerpt from Svabhava: Its Heretical Roots

Svabhāva is the key ontological notion that defines and explains ‘existence/non-existence’ in Buddhism. It asks, ‘what it means to exist?’ or ‘to not exist (śūnyatā)’. Svabhāva has been variedly interpreted in different philosophical contexts across various sects within Buddhism. According to Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka, śūnyatā or emptiness is linked with the concept of svabhāva. Svabhāva, often translated as ‘inherent existence’ or ‘inherent essence’ has two senses from which it can be understood one from an ontological perspective and second from a cognitive perspective. From an ontological perspective, it can be understood in terms of the way things exist such as ‘essence’, ‘substance’ or ‘ultimate reality’ and from the perspective of cognition it can be understood as the way by which things are conceptualized by the human being. Śūnyatā and Svabhāva are interconnected in the ontological sense that Śūnyatā means lacking inherent essence (svabhāva) or ‘self-nature’, but from a cognitive or phenomenal perspective svabhāva means the property or quality (svalakṣaṇa) of an object that makes it that object and not some other object, for instance, the svabhāva of fire is heat, of water is motion and so on. So according to the doctrine of emptiness, all things including human beings lack an inherent or independent essence because they are all interdependent on something else for their existence.

While the early Madhyamaka texts like the Prajñāparāmitasūtra, deny the existence of any svabhāva within any being along the lines of the doctrine of emptiness or Śūnyatā, the later texts speak of the existence of an inherent self-nature svabhāva of all things. The Abhidhamma literature makes a distinction between svabhāva as a dependent, irreducible, momentary phenomena (Dhamma) which is distinguished from conventional objects which are conceptually constructed. They later go on to explain and elaborate on what constitutes the true Buddha nature or svabhāva.

Typically, it is argued that the doctrine of svabhāva is responsible for the conception of materialism in Indian thought called Svabhāvavāda which is associated with the Cārvāka/ Lokāyata schools[1]. For the Cārvāka, Svabhāva meant the ‘laws of nature’[2] which is synonymous with causality (hetu). Svabhāva is the first cause (jagatkāraṇa) which is distinct from a creator God or an uncaused entity or thing.

But contrary to this view, the Buddhist philosopher Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita composed in 2nd century A.D, where he equates Svabhāva with yadṛchhā (ahetu) translated as ‘accidental’ or ‘chance’. When svabhāva is conceived as ‘accidental’ then it goes against the notion of causality because that which is accidental or determined by chance has no prior or antecedent cause. The first known doxography and poetry, written by the Tamil poet Cāttaṇār’s Maṇimekalai (3rd century A.D.) speaks about the school of Bhūtavāda as one of the atheistic systems that assigns svabhāva to accidentalism or yadṛchhā.

~~~

[1] According to Bṛhat saṁhita (1.7), self-nature (svabhāva) is the cause of the world. Gokhale, P. P. (2015). Lokāyata/Cārvāka: A Philosophical Inquiry. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

[2] The ‘laws of nature’ or the ‘order of nature’ which describes the way in which nature works. The term used in the Rig Veda for ‘laws of nature’ is Ṛta, which is also translated as universal law or cosmic order. The Ṛta is not just tied to natural law but also includes moral and sacrificial orders. It is inclusive of the rules and ritual obligations of the individual collectively referred to as the Dharma. Buddhism, on the other hand, the ‘laws of nature’ does not include the individuals moral and sacrificial or ritual orders or the hierarchical ordering of nature, but rather how the human being like all other objects are interdependent on each other for their existence also called Pratītyasamutpāda or doctrine of dependent origination. So, therefore there is nothing that exists on its own but has come from earlier circumstances or conditions, everything including man, the world is interwoven. The laws of nature in Vedas is prescriptive while in Buddhism it is descriptive.

Please read the full article on Prabuddha: Journal of Social Equality.

~~~

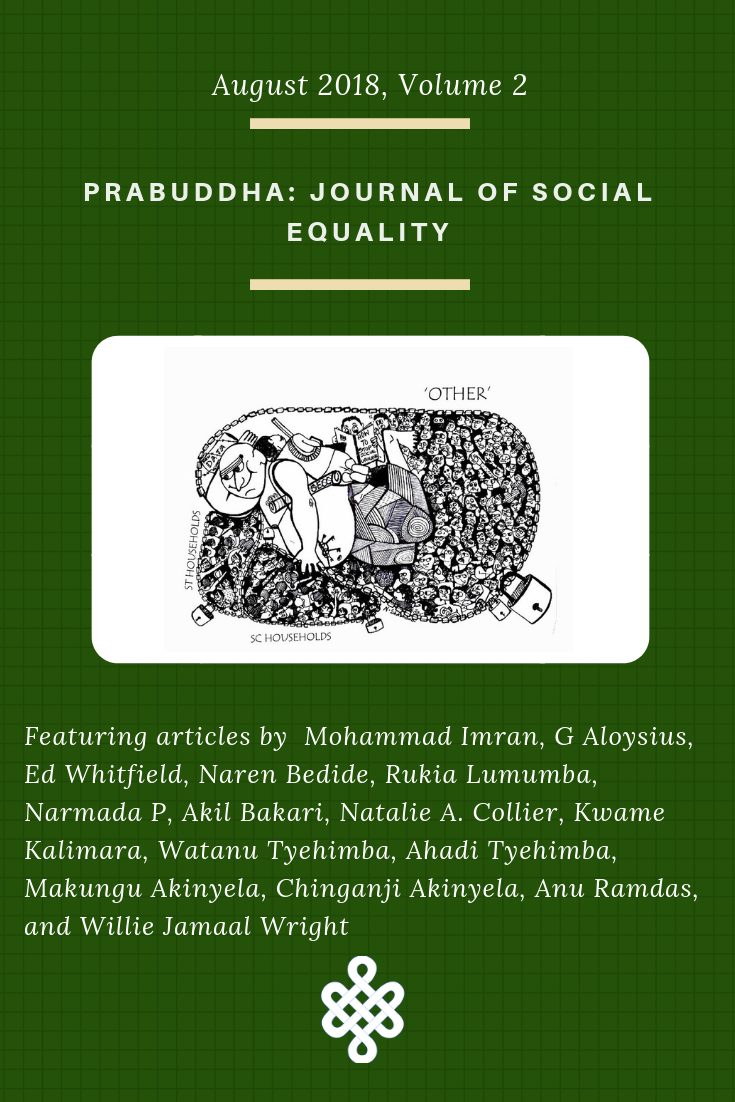

Note: The second issue of Prabuddha: Journal of Social Equality carries articles by women authors from anti-caste traditions and black liberation movements exploring the myths of inherent essence or “svabhava” of humans. Authors from the anti-caste traditions examine ‘The Brahmin Svabhava—uninterrupted access to surplus, labor, and property over the ages.’ And authors from Black liberation movements examine ‘White supremacy and its uninterrupted access to surplus, labor, and property over the ages.’ SAVARI is happy to share excerpts from their articles.