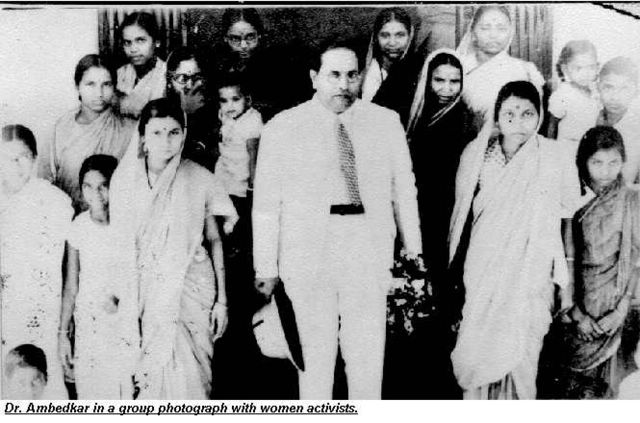

Recently, the Indian Parliament approved an amendment to the Maternity Benefit Bill 2016 that raised maternity leave to 26 weeks from 12 weeks for women working in the organized sector. Maternity Benefit was legally introduced in India for the first time in the Bombay Legislative Council. Dr Ambedkar supported and defended it. It is instructive to revisit his arguments in the Bombay Legislative Council in 1928.

Celebrating his 126th Birthday, we reproduce a section from Volume 2 of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and speeches compiled and Edited by Vasant Moon and published by the Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra in 1982. This section is sourced from B.L.C. Debates, Vol. XXIII, pp. 381-82, dated 28th July 1928.

We take this opportunity to wish Ambedkarites across the world a Happy 126th Ambedkar Jayanti!

—

ON MATERNITY BENEFIT BILL

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar: Sir, I rise to support the first reading of this bill. And in doing so I just wish to reply to a few points that have been raised in the course of this debate against this bill. The Honourable the General Member, in speaking against the bill, first of all, pointed out that this is not an accident—accident as we understand it under the Workmen’s Compensation Act, and, therefore, the principle of the Workmen’s Compensation Act cannot be extended to the women who would be entitled to get the benefit under this particular bill. I admit, Sir, that this is not an accident. But it does not follow from that, that women are not entitled to get the benefit which the proposed bill desire to confer upon them. The principle on which this bill is based is altogether biased. There is absolutely, I believe, unanimity on this proposition that the pre-natal conditions which affect the mother are an important factor in the bill and the subsequent bringing up of the child. I do not think anybody will controvert that proposition. And I believe, therefore, Sir, that it is in the interests of the nation that the mother ought to get a certain amount of rest during the pre-natal period and also subsequently, and the principle of the bill is based entirely on that principle. That being so, Sir, I am bound to admit that the burden of this ought to be largely borne by the Government. I am prepared to admit this fact because the conservation of the people’s welfare is primarily the concern of the Government. And in every country, therefore, where the maternity benefit has been introduced, you will find that the Government has been subjected to a certain amount of charge with regard to maternity benefit.

But that being so, Sir, I am not prepared to admit that the employer who employs a woman, under such circumstances, is altogether free from the liability of such benefit in the interests of the woman and the reason for this is this. There is no doubt that an employer employs women in certain industries because he finds that there is a greater profit to be gained by him by the employment of women than he would gain by the employment of men. He is able to get pro rata larger benefits out of women than he would get by employing men. That being so, it is absolutely reasonable to say that to a certain extent at least the employer will be liable for this kind of benefit when he gets a special benefit by employing women instead of men. I, therefore, say that although there ought to have been some liability imposed on the Government in the matter of maternity benefit, I think the bill is not altogether wrong if it seeks to impose the liability under the present circumstances on the employer. I, therefore, support the bill on that account.

It is stated that this bill is applied only to factories and not to other industries or to the agricultural occupation. The reply to that is very simple. It is to those industries where the conditions are such that they particularly affect the health of a woman that this principle is extended. In agriculture and other occupations the women are not exposed to those dangers or to those factors which obtain in factories and which affect the health of the women working in those factories. That is the reason why, for instance, such legislation is usually confined only to factories. The same may be said, for instance, with regard to the Workmen’s Compensation Act. That Act applies to accident which may arise in factories in the course of the employment of labour for this very reason, and you will find that legislation is confined only to factories and not to other occupations.

Now, in respect of the burden on industries, the Honourable the General Member said that it will result in the reduction of wages. I am not certain whether it will result in a reduction of wages. Even if it does, it will mean that the burden on the industries will to a certain extent be shifted elsewhere and the Honourable the General Member ought therefore to have no objection on that ground. If this bill is passed, my submission is that the burden will probably be shifted on to the consumer and if it is shifted on to the consumer, the society as such ought not to object to pay the larger price for the produce in order that the producers who produce it may be benefitted.

Then, it is said that it is unjust to confine this bill to the Bombay Presidency only and that it ought to be extended to the whole of India, and that other Presidencies and provinces in India ought to be put on a par with the Bombay Presidency. My submission to you, Sir, is this. Suppose that this bill is applied to the whole of British India, what is there to prevent somebody rising up and saying, “Why should this bill be confined to India only and not to other countries? India will be put at a disadvantage with respect to the other countries of the world and therefore let us wait till the whole world adopts the principle of this bill and then we may all be on a par with each other”. I submit that there is no substance in this argument and I think, therefore, the benefits contemplated by this bill ought to be given by this Legislature to the poor women who toil in our factories in this Presidency.