Rupali Bansode

Entering the academic space is not an easy journey for Dalit women. After studying in social science institutions and reading/learning theories about gender and women, there is a phase when self-reflection becomes necessary. In fact, reflexivity is considered very important in feminist research methodology. Taking this into consideration, this note is an attempt towards assembling a few shared experiences of Dalit girls in the discipline of Women’s Studies.

Known debates between Feminists and Dalit Women

Caste based structural oppression in India is faced by Dalits in general and Dalit women in particular and this has been voiced multiple times by Dalits as well as non-Dalit academicians and theorists. The academic discipline of Women’s Studies where sisterhood is celebrated has faced much accusation from Dalit women activists and writers, for serving only the ‘upper-caste/class feminists’ needs and ‘not doing justice to Dalit women’s perspectives’. The silence from non-Dalit practitioners on the rape cases in Haryana and Bihar outraged many Dalit women’s groups. And Dalit women’s groups are accused of not pointing out their grievances about Dalit patriarchy. Such a tussle is going on between feminists and Dalit women for more than two decades.

Adjusting for survival

Like in all communities, early marriage as a system prevails in the Dalit communities too; and boys get more attention than girls as in other communities. Dalit girls with the inspiration to study further have to negotiate with such patriarchal prejudices and practices within and outside the community. It is in this context that we should talk about the prospect of Dalit women in the academic discipline of Women’s Studies.

Women’s Studies is criticized for being an ‘elite’ women’s arena and not a Dalit girls ‘cup of tea’. Dalit girls are considered as incapable of pursuing their career in this discipline. Such kind of thinking towards Dalit girls prevails both within and outside the community, and it sometimes leads to their emotional breakdown and provides them with a greater determination to fight, at other times.

Many a time Dalit girls who enter the discipline of Women’s Studies are from vernacular medium backgrounds or from non-standard English medium schools. In such conditions, it becomes difficult for them to immediately grasp the context of the many theories and the curriculum. Often the journey of Dalit girls starts with adapting to, and learning English. Most of their study time goes in translating difficult English words into their own local language and then understanding their contexts. This phase begins from the day they start attending classes and lasts till the point they complete their dissertation, and then continues later on if they decide to carry on their career in this field. In fact, Dalit girls have to be more attentive in the class and need to do more hard work for acquiring knowledge. There are a few Centers with sensitive faculty members who work hard in leveling the ground, and raising confidence levels of these students, by adopting strategies like translating textbook material or conducting discussions which help students to understand the context and the gist of a given article. However, this is not always the case.

Another huge problem is that feminism as a discipline is considered as a westernized model and in many social sciences campuses, students and faculties doing Women/Gender Studies are considered as ‘man-haters’ and as ‘women who do not believe in family’ or they are branded as ‘lesbians’. Such terminologies against the discipline put Dalit girls in a paradox and they face dual criticism as seen earlier. At times it’s a strike on their identity. Very often they are blamed for being ‘rude-arrogant’ Ambedkarite/Dalit-Women/Feminists who are trying to be like Upper-caste/class feminists. They are then shown the mirror and told that they will be ‘Dalit women’ and ‘women’ at the end of the day.

To move away from these criticisms and contradictory opinions becomes difficult, and at times Dalit girls who get trapped in these discussions lose their focus and even lose interest in their studies. At times the social location of other students in this discipline makes Dalit girls feel isolated and they are not able to have any dialogue with other fellow students. Later on, this kind of tendencies are found in their workplaces too. It is a continuous process of adjustment marked with several points of breakdown. At such moments, it is the men and women from the community who come to support them and help them get them back on track.

More importantly, the curriculum of the Women’s Studies discipline does not reflect the shared history of Dalit girls. If one considers the context of Maharashtra, many writings in the form of both prose and poetry, by Dalit intellectuals like Daya Pawar, Jyoti Lanjewar, Kumud Pawade and others, goes unfeatured. The history made, written and shared by these women are neither discussed nor taught.

Even the readings in this discipline differ from center to center. A few centers focus on Women’s movement in the Indian context whereas other centers focus on readings in the western milieu. Lives and struggles of the women leaders and intellectuals from Dalit communities goes unmentioned, alienating the Dalit girl students, and at times they feel that this discipline is not for them. Yet, there are other pointers which they can identify with.

In the end, they are left with these questions. What belongs to them? Which field? Such problems and tendencies are present in the mainstream and other disciplines too. No field will keep them away from alienation and marginalization. Caste as a factor is so entrenched in Indian society that to understand this oppression one has to look at the structural levels – from the remote areas to the urban areas and till the academic discipline, where theories are generated and then propagated. Dalit girls feel there is nothing called ‘Sisterhood’, nothing called ‘Oneness’, rather they feel excluded always.

This discipline faces many problems, which are reproduced by its practitioners, and Dalit girls have to make lots of adjustments to enter and survive in this discipline. They have to face challenges from within as well as outside the discipline – from the community and from outside the community. We still go back to the same question of what can be done in this context? One suggestion can be of increasing the quantum of Dalit girls in this discipline- in future this can increase the number of Dalit women faculty in the departments; restructuring of courses on feminism; inviting Dalit intellectuals as visiting faculty to teach specific subjects like caste and gender, education, livelihood, Dalit Feminism, Dalit women’s movement etc. Students can exchange their ideas with them and this can help in sensitizing the members in the field of social sciences towards both Dalit and non-Dalit students.

~~~

Rupali Bansode holds a Masters degree from TISS and currently works with Columbia Global Centers, South Asia in Mumbai.

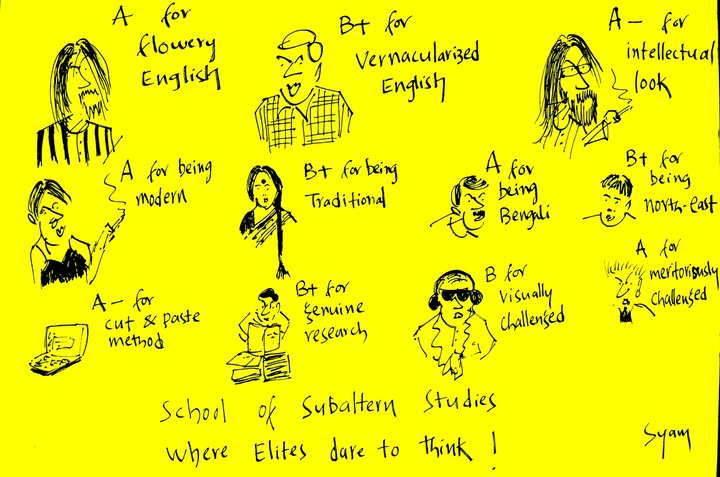

Cartoon by Unnamati Syama Sundar.

This article is also published in Round Table India.

Very critical issues have been raised! However, its not true that writings of Daya Pawar, Jyoti Lanjewar, Kumud Pawade and others goes unfeatured. Its only minimal in comparison to upper-caste writers for sure but writings of Kumud Pawde, Urmila Pawar, Jyoti Lanjewal and more have been recognised in some of the Universities in India. Their work has been included as an important reading in the syllabus

Very well written, Rupali.

‘Sisterhood’ is indeed a myth. Caste is an important discourse and gender cannot/should not be studied in isolation. WS as a discipline needs to be saved from this pitfall. The saving grace is, it is called ‘Women Studies’ and not ‘Feminist Studies’ — that gives it broader leeway to bring in Dalit experiences and help construct specific epistemologies. Universality is a wrong thing to be sought here… and this must be driven home by participants (students, teachers) in this discipline. The process is slow but it is not a lost cause.

Very well written.This is a true portrayal of the unseen side of our elitist institutions,something which i have experienced.

Hi. I wish I could help. I am a Muslim in the UK and feel so frustrated not to help a single dalit in my life