Priya Chandran

The rape and murder of 23 year old student Jyoti, in Delhi, which has brought out a tremendous response from the middle class Delhi public and later from similar urban categories across the country also gained considerable media attention. When the immediate affective reaction of this public varied from demanding capital punishment for the rapists, to demands for providing better security for women at all times, a few articles that came in newspapers and blogs tried to deal with the issue at relatively deeper levels. Along with these voices, feebly though, another voice could also be heard which asked the new infuriated public where it was when the dalit and lower caste women were brutally attacked?

In the very minute instance where media let this question through, it also did not forget to answer this question from the perspective of the same middle class public which it represents and is composed of. As the spokesperson of the urban middle class, media suggests that such a question is insignificant because now what is important is that “women” across the country come out to protest against this “women’s problem”. In the context of these discussions, I would like to point out a few things that would throw light into the way a certain blind spot has been historically created in the minds of upper caste and also lower caste middle classes, and how this blind spot has been historically preventing the “public” from listening to or understanding the dalit, lower caste perspective.

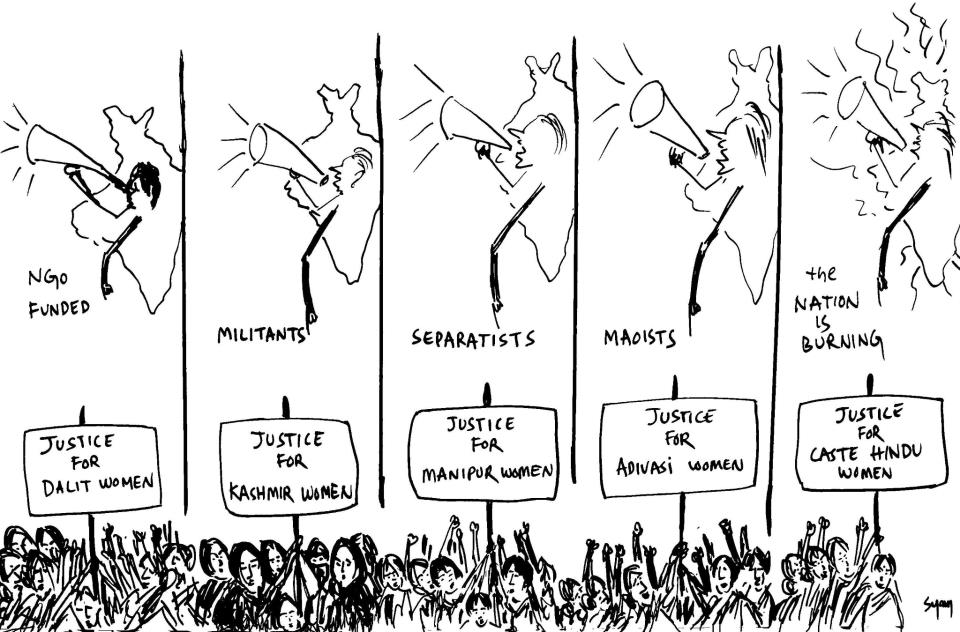

I would like to make it clear in the beginning itself that I am not saying the spontaneous middle class response in Delhi is by itself despicable. Instead I am happy that such a crowd came out in support of a case like this. But if the responses to this case stop with guessing, suggesting or implementing immediate solutions to an easily identified problem, would it cause much change in the way our society functions? In the collective imagination of the Indian public the case acquired the status of a common issue. What I mean by calling it a common issue is that unlike the cases of violence against women in Chhattisgarh, Assam, Haryana and in many other places on a daily scale, it is an issue with which a majority of Indians could identify or at least the media presented it in such a way. When in a dalit- lower caste perspective a question arises in this scenario pointing to the invisibility of problems faced by dalit, bahujan and adivasi women, it needs to be listened to, and contemplated as it is also a part of the many perspectives that come out of the response. Media and newspapers not only ignore any such voice but also manipulate it to have an unintended and negative influence on the society.

When in any lower caste voice a problem is raised that points to their specific social and political location in a country that takes pride in the democratic power of its people, the media and the middle class public that they represent ignore such voices by making this category of Indian society invisible and inaudible at the level of the state. This is an ultimate denial of the democratic space through social structures. The Indian democracy constitutes only a certain middle class (where the lower caste people have shed their caste identity for the sake of social/class acceptance) voice that comes in the garb of ‘nation’s voice’. This means that the present political structures are not enough to deal with the problem of caste/class/ gender inequalities in the country.

“What is the problem with considering rape and other sorts of violence against women as one? After all women are women and rape is rape!” This is the point many people raise when responding to the lower caste question on violence against women. Let us look at this argument and see what problem it has. When highlighting the difference in the way the recent Delhi rape is dealt with from that of continuing series of violence against dalit, adivasi, bahujan women one does not mean that the former is wrong. Instead, the point is that if all kinds of violence against women are perceived and conceptualized from the perspective of a middle class which has gathered in Delhi in the context of the rape and murder of Jyoti, it is natural for even the Prime Minister to say that poor people who come from rural areas to Delhi, and do not get absorbed by the developmental programs, are a social menace. Here as far as the conceptualization goes in many minds it seems in the first glance that an innocent girl gets raped and murdered by the criminal poor. This shows that the identification of a problem and the social/political location in which the problem is identified can be seriously influenced by the self-identification and social/cultural/political location of the perceiver.

When a social issue of this scale is understood just based on a single episode of a series of such incidents in different circumstances happening to people in different class/caste/gender locations, a problem is too easily conceptualized, its victim and its perpetrator are easily identified based on this single perspective. This is very evident in various expressions of rage and support in social media where the girl is constructed as a fragile entity being attacked by some brutal, ignorant men. It fits well with the oldest narratives of violence against women and hence does not change the subtle discursive practices that have been historically perpetuating inequality among people. So the sudden rage that took many out into the streets of Delhi may also be understood as a problem and not (yet) a “solution” as some would call it.

~~~~

Priya Chandran is a research scholar in the Department of Cultural Studies at the English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU), Hyderabad.

Cartoon By Unnamati Syama Sundar.